Understanding Charles Sanders Peirce: The Nature of Belief

Written on

Chapter 1: The Foundations of Peirce's Philosophy

The essence of our existence lies in our beliefs, making the processes through which we form them critical to our understanding.

Peirce: A Pragmatic Visionary

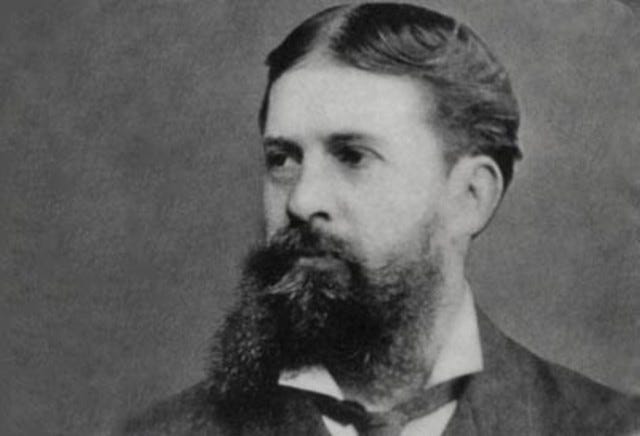

Charles Sanders Peirce (1839–1914) was a pivotal figure in developing pragmatism, aiming to enhance the precision of scientific inquiry in its quest for truth. His groundbreaking philosophical framework established a new philosophical school. Primarily a physical scientist, Peirce dedicated over three decades to investigating subtle variations in the Earth’s gravitational field. His commitment to precise measurements and thorough data interpretation profoundly influenced his philosophical outlook.

Peirce approached the question of truth from various angles. He revived the notion that words function as signs, an idea first popularized by John Duns Scotus, which later inspired William of Ockham’s nominalism. Peirce, drawing from thinkers like John, William, and Immanuel Kant, advanced this concept by introducing "semiotics," the study of signs and their formal application. Traditionally, signs were understood in a binary framework of signifier (the word) and signified (the concept the word represents), a view shared by John, William, Augustine, and later by linguist Ferdinand de Saussure (1857–1913).

Peirce expanded on this by introducing the "interpretant," a societal framework of meanings that interprets signifiers. Symbols are effective because interpretants connect them to their meanings. A flag, for instance, is merely fabric until the shared social meanings and emotions associated with it imbue it with significance. Each sign generates further signs that help clarify their usage. To grasp the interpretant concept, consider a dictionary; it employs words to define other words.

Peirce asserted that our universe is saturated with signs, forming a complex web that shapes both individual and collective consciousness. A society is a tapestry of signs, symbols, meanings, and interpretations that continuously interact in an evolving interpretation of objects and ideas. Our language of signs is dynamic, constantly reshaping our understanding of truth. This perspective on sign functionality informed Peirce's pragmatist definition of truth.

Another dimension of Peirce's exploration of truth involved examining the practical implications of our perceptions of objects, as these perceptions encompass our entire understanding of them. Essentially, we define an object by its perceived effects or the actions we can undertake with it. This viewpoint signifies a departure from speculative philosophy, as seen in Kant’s work, while simultaneously affirming that our concepts must be subject to testing. Peirce asserted that if an object's quality or concept is not testable, then our understanding of it is devoid of meaning. This principle forms the core of Peirce's pragmatism, which emphasizes experience. As philosophers and scientists, it is imperative to concentrate on the practical, testable outcomes of objects; anything less is inconsequential.

Peirce recognized that what we label as "truths" are fundamentally beliefs. He posited that a list of our perceived truths aligns with our beliefs. He characterized beliefs as conscious states that alleviate doubt and foster habitual responses. This notion echoes Hume’s insights; however, Peirce underscored that our beliefs, as habits, are interlinked with physical actions or psychological expectations. Our habitual responses shape our interactions with the external world.

Despite his scientific background, Peirce acknowledged that we are ultimately confined to our beliefs about reality. His focus on mathematics and empirical science limited his exploration of the broader societal implications of belief formation. Nevertheless, he laid a robust foundation for understanding how we cultivate and sustain particular beliefs.

The Process of Fixating Beliefs

In his 1877 article, "The Fixation of Belief," Peirce elucidated the mechanisms through which we establish habitual beliefs and how they become entrenched in our minds. He began by explaining the function of beliefs, stating that they guide our desires and influence our actions, creating psychological states that dictate our behaviors. To believe in something or someone instills habits that condition our responses.

Similar to Hume, Peirce accepted that our truths are shaped by habits, viewing them positively as long as they yield beneficial practical outcomes. For instance, believing in a leader fosters a tendency to obey, under the assumption that such obedience will lead to favorable results. Peirce distinguished belief from doubt, defining belief as a stable and satisfying mental state that we seek to maintain. In contrast, doubt represents a disquieting and unsatisfactory state we strive to escape.

To illustrate Peirce's point, consider the analogy of comfortable shoes: if they become uncomfortable due to damage, we either repair them or seek new ones. The discomfort of doubt serves as a crucial learning tool. While Descartes employed doubt as a pathway to certainty, Peirce focused on acquiring practical knowledge. Our beliefs are not exact mirrors of truth, and we err in thinking they are. Instead, our beliefs should be subject to continual self-correction based on our experiences, guiding us toward beliefs of practical significance.

Peirce argued that we should remain receptive to doubt, as it encourages us to critically evaluate our beliefs, discard unsatisfactory ones, and strive for new beliefs that foster improved habits and outcomes. However, he noted that this ideal is not always realized in practice.

Peirce outlined four methods through which we alleviate the discomfort of doubt and solidify our beliefs, ranking them from least to most favorable. The initial method is rooted in the instinctive aversion to uncertainty, which leads individuals to cling tightly to existing beliefs. This approach, which he termed "the method of tenacity," is inherently unstable, as it often encounters contradictory evidence and differing viewpoints. Nonetheless, this method remains prevalent, with individuals attempting to silence doubt by disregarding any evidence that challenges their beliefs.

Peirce identified a second method, operating at the community level, known as "the method of authority." This approach has been adopted by numerous civilizations, establishing a set of accepted doctrines taught to the populace. While it promotes a cohesive belief system within a community, it also mirrors the method of tenacity on a larger scale. This method proves unsustainable, as no institution can monitor every individual's beliefs. Peirce likens this to Ibn Rushd's perspective, suggesting that this method governs those lacking the drive for intellectual independence.

The third method involves holding opinions aligned with reason, which Peirce refers to as "the a priori method." This approach, rooted in the philosophical belief in knowledge independent of experience, yields mere opinions rather than evidence-based conclusions. Peirce criticized many philosophers for relying on this method, arguing it reduces inquiry to subjective matters of taste. The a priori method ultimately devolves into a collection of intellectual biases.

The limitations of these three methods underscore the necessity of identifying an effective approach for establishing beliefs. Since beliefs are essential for functioning, the objective is to discover those that yield positive, tangible results. Peirce advocated for a method of belief fixation that is not solely personal but is grounded in external realities—an approach characterized by "the method of science." This entails employing our active minds to systematically observe the world independently of our subjective thoughts, beginning with observable facts and progressing toward the unknown. The evidence, rather than personal inclinations, should guide our beliefs.

An openness to questioning our beliefs is vital for genuine inquiry. While the desire for comfort and habitual thinking may tempt us, critical reflection on the facts can counter these inclinations. The scientific method is inherently flexible, allowing evidence to shape our understanding, thereby ensuring that our beliefs respond to the world rather than our biases.

Science and Collective Understanding

Peirce fundamentally disagreed with the notion, prevalent among many philosophers and scientists, that the universe is static and entirely predictable. He maintained that the universe is in a constant state of flux, exhibiting elements of randomness alongside apparent order. A similar perspective is echoed in the works of Henri Bergson.

In "Fixation of Belief," Peirce grappled with the complexities of human subjectivity. His 1878 article, "How to Make Our Ideas Clear," addressed the challenges of navigating a universe filled with chance.

Peirce argued that the meanings of our beliefs are shaped through our interactions with the world, which are observable in a public context. The actions we take define the meanings of signs and beliefs, emphasizing the performative and communal nature of meaning. This public dimension is crucial; while our beliefs are all we possess, they cannot be deemed real or true without connecting to evidence.

Determining reality hinges on collective human effort, as individual beliefs alone do not dictate what is real. For Peirce, science serves as the bridge between meaning, truth, and reality. He believed that although one person may err in their beliefs, humanity, through collaborative effort, can arrive at a shared understanding of reality.

The truth is defined as the consensus ultimately reached by all who investigate, while the reality represented by this consensus reflects what exists independent of individual beliefs. Peirce’s ideas parallel Hegel's in that knowledge transitions from incomplete to more comprehensive understandings, but Peirce's approach is more grounded in scientific observation than Hegel’s philosophical constructs.

Peirce’s influence on scientific methods may have been less direct than he envisioned, but he significantly impacted his contemporaries, including William James.

The video "How We Come to Our Beliefs: Charles Sanders Peirce on The Fixation of Belief" delves into Peirce's examination of how beliefs are formed and established in our minds, shedding light on his philosophical contributions.

In "The Fixation of Belief - Charles Peirce," viewers can further explore Peirce's insights on the nature of belief, how it guides our actions, and the methods we use to solidify our beliefs.