Embracing the Legacy of Longleaf Pines in Central Florida

Written on

Chapter 1: The Majestic Longleaf Pine

In my neighbor's yard stands a longleaf pine tree, a towering presence that leans slightly toward my backyard, as if intrigued by my daily activities—whether I'm chatting with my dogs or enjoying sunny afternoons. This tree serves as a shelter for pine warblers, owls, and hummingbirds that dart through my space. I often ponder its past, wondering how long it has stood sentinel and what stories it might tell. In the words of Victor Hugo, “What is history? An echo of the past in the future; a reflex from the future on the past.”

The neighborhood I call home in Central Florida emerged in the early 1970s, thanks to developer E. Everett Huskey, who recognized that elevation and trees were treasures to be preserved rather than obstacles to be removed. He designed winding roads to protect existing groves of trees. In a 1987 interview with the Orlando Sentinel, he noted that the land was untouched before his development, with no orange groves to be found.

Yet, beneath the surface, history was already unfolding.

Section 1.1: A Journey Back in Time

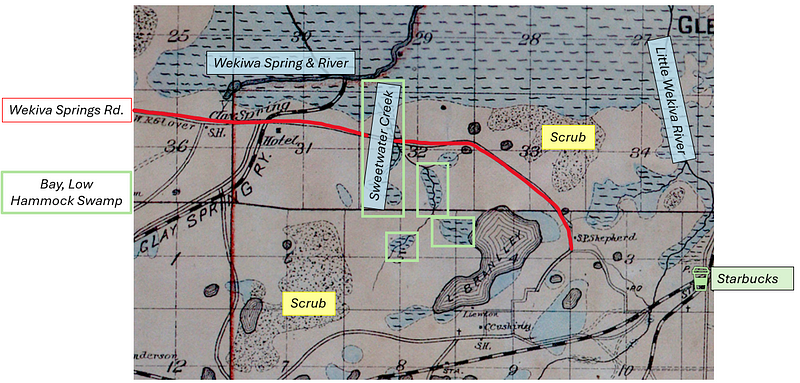

Rewind to 1890, when the area now known as Wekiwa Springs was beginning to thrive. Small towns emerged alongside the burgeoning cities of Orlando, Tampa, and Daytona Beach. Apopka, located northwest of Orlando, began to attract visitors to its lively springs, initially called Clay Spring, which were believed to possess healing qualities. This spring fed into the Wekiva River, which eventually joins the St. John’s River.

In 1887, a hotel was established near Clay Spring, operating until the 1930s. Roads and railroads were constructed to accommodate travelers heading to Apopka, further shaping the landscape. The first complete map of the area dates back to 1890.

Noteworthy details from the 1890 survey include:

- The road layout has remained consistent for over a century.

- The railroad has vanished, but the road continues to connect nearby suburbs and towns.

- A post office once stood at the convergence of two rail lines, now a Starbucks.

- Low hammock swamps have largely remained intact, while golf courses now occupy former scrub ecosystems.

- Areas not marked likely consist of pine flatwoods and sandhills, favored by developers for clearing.

Section 1.2: The Industrial Boom

As the early 1900s rolled in, the region experienced industrial growth. Northeastern residents flocked south, establishing winter homes, while real estate moguls erected hotels and railroads to cater to the influx of visitors. The nation also found itself embroiled in wars, necessitating a larger naval fleet.

What connected these hotels, railways, and homes? The answer was timber.

The Wilson Cypress Company, founded in Palatka in 1893, quickly became the world’s second-largest cypress mill, logging the Wekiwa Springs area for cypress, pine, and hardwoods.

Before felling the trees, they would tap them for sap, which was boiled down to produce turpentine. This oil was essential for making ships watertight and preserving ropes. Tapping involved cutting V-shaped grooves into the bark and installing metal strips to channel the sap into containers at the base of the tree. Over time, these scars resembled a cat’s face.

The Wilson Cypress Company ceased operations in Florida in 1944, selling their land to the Apopka Sportsmen’s Club, which later became Wekiwa Springs State Park, ensuring the preservation of the spring, river, and surrounding ecosystems for future generations.

Chapter 2: Resilience of Nature

Hope and Restoration: Saving the Whitebark Pine

This video explores efforts to protect and restore the whitebark pine, a vital species in its ecosystem.

Save the Whitebark Pine: Film Screening and Expert Panel

Watch as experts discuss the importance of whitebark pine and the initiatives aimed at its conservation.

The landscape has undergone tremendous changes since the Wilson Cypress left in the 1940s. While some pines were cut down, many remain standing today, including six in a one-block radius of my home, each marked with scars from past logging activities. One tree even still bears the nails and metal strips used for sap collection.

It's astonishing to think that loggers once traversed my property in search of the perfect pine. The resilience of these trees is remarkable; despite enduring the extraction of their sap, they continue to thrive, providing shade and habitats for a variety of wildlife.

Hope for the future

While I haven't examined the base of the longleaf pine in my backyard for scars, I know it has witnessed countless events throughout its life. I appreciate that the developer of my neighborhood recognized the value of preserving some of the original landscape. Longleaf pines can live for over 200 years, and their forests once spanned across the Southeast, covering 90 million acres. Regrettably, only 3% of these forests remain today, threatened by development, climate change, and careless tree removal.

These magnificent trees inspire awe with their height and grandeur, offering sturdy branches for nesting birds of prey, while their expansive canopies provide much-needed shade, reducing energy costs and enhancing outdoor experiences.

Although no pines were on my property when I moved in, I have adopted my neighbor's tree in spirit and planted two pines in my yard. They take time to grow, so I may not be around to see them reach maturity. However, if future inhabitants care for them, they too might uncover the secrets these pines hold.

Karen McLaughlin is a corporate expat embarking on a solopreneurial journey, sharing her insights on nature, self-improvement, and leadership. For more stories about Florida's flora and fauna, join her on Florida Native.