# The Counting Methods of Ancient Romans and Their Legacy

Written on

Chapter 1: Roman Numerals and Their Endurance

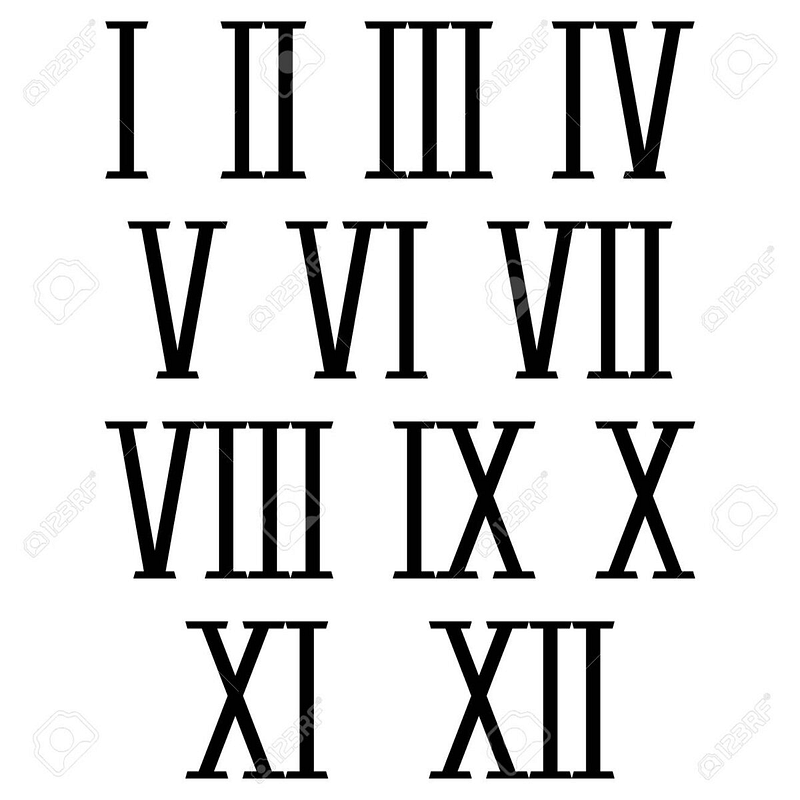

Roman numerals have persisted through time and are still in use today, albeit less frequently than the more commonly recognized Arabic numerals. The ancient Greeks also employed a numeral system that used letters to represent numbers, but this has since faded into obscurity. In contrast, the Romans utilized a more concise system with only seven symbols: I (1), V (5), X (10), L (50), C (100), D (500), and M (1000). To denote larger numbers, a horizontal line was placed over the numeral—indicating that V represented 5,000 and M represented one million. Although two bars over V signified 5 million, such large figures were rare in Roman transactions.

An inscription on an ancient Roman tombstone reveals the deceased's age—XXVII (27 years). Scholars generally agree that the Romans adapted their numeral system from the Etruscans, although there is no definitive explanation as to why these specific letters were chosen. One hypothesis suggests that the numeral V symbolizes an open hand with four fingers together and the thumb extended, while X represents two hands crossed or a doubled V. The letters C and M may relate to the initial letters of the Latin words for 100 (centum) and 1000 (mille). Notably, the numeral for “four” was historically written as “IIII” until the 19th century, when “IV” became the norm.

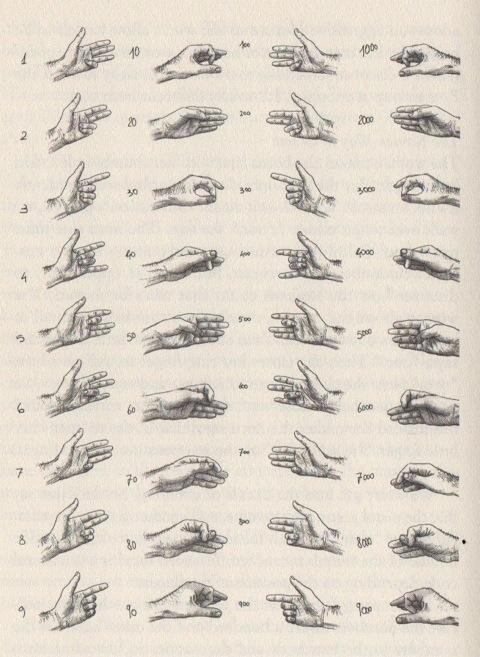

Counting to a thousand using fingers was a straightforward method employed by the ancient Romans. They used one hand for counting up to a hundred and the other to signify hundreds and thousands, allowing them to express any number up to ten thousand. This technique sufficed for everyday transactions, such as calculating market prices.

This finger-counting method is even depicted in sculptures. Ancient scholar Pliny the Elder noted that the statue of Janus illustrated the number of days in a year—365—using both hands.

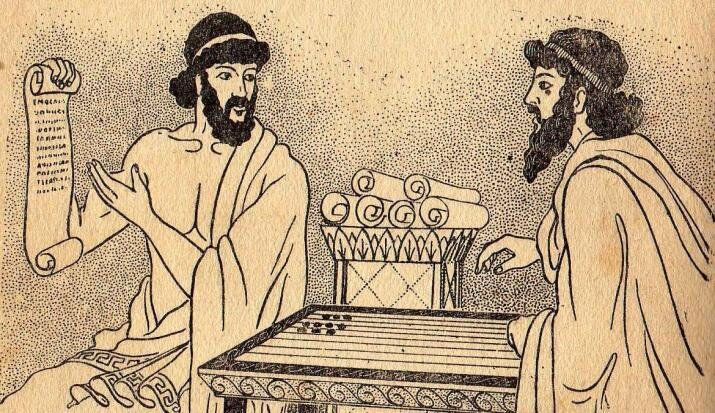

Despite the simplicity of finger counting, it is prone to mistakes. A more reliable method involved writing calculations with a stylus on a wax-covered tablet. Additionally, the ancient Babylonians developed the abacus—a counting board with pebbles—around the 3rd millennium BC. Initially, it consisted of a board divided into sections, each containing a corresponding number of pebbles. However, any abrupt movement could displace the pebbles, prompting the creation of depressions in the board's sections to keep the pebbles aligned.

By the 5th century BC, Egyptians innovated by using wire threaded with perforated pebbles or small bones instead of depressions, enhancing the design of the abacus, which remained in use until the 20th century. The Roman version of the abacus was a compact plate featuring slots for metal chips. Notably, the Roman counting system differed from others; instead of ten chips, they used four and one (in a separate slot), symbolizing the number five.

Unlike the Greeks and Indians, who developed intricate mathematical systems, the Romans did not prioritize abstract calculations. Thus, they found the abacus and wax tablets sufficient for their needs. On parchment or papyrus imported from Egypt, Romans typically recorded only the results of calculations rather than the processes involved. Furthermore, they preferred simple fractions, limiting their use to those no more complex than 1/12. This preference meant that the challenges posed by Roman numerals did not hinder their ability to perform basic calculations.

The Romans were aware of the concept of zero, having learned about it from Greek philosophers. The term they used, “nullus,” meant “none,” yet they lacked a numeral for zero. The Romans did not see the need for a specific symbol to represent nothing, considering it an abstract idea without practical use until the introduction of Arabic numerals and the positional number system, which necessitated its inclusion.

If you’re interested in more historical insights, don’t forget to like and subscribe to our channel!