A Prescription for Awe: The Intersection of Science and Faith

Written on

Chapter 1: The Journey Begins

With our heads down, we trudged along a coastal path against a fierce wind that roared up the English Channel, pelting rain against our faces. Our first goal was Durdle Door, a stunning natural arch overlooking the sea. Despite the relentless downpour of what was already a record-breaking wet summer in England, the adventure only heightened our spirits. Together with my wife, Anne Harrington, a historian of science at Harvard University, I was leading 15 students from the Harvard Summer School on an exploration of England’s Jurassic Coast. This nearly 100-mile stretch of fossil-rich rocks has significantly influenced the founding principles of historical geology over the past two centuries.

Few places on Earth are as scientifically revealing as this coast. The rock layers along the Jurassic Coast form a nearly continuous sequence that spans from the early Triassic period—around 250 million years ago—through to the end of the dinosaurs in the late Cretaceous, roughly 65 million years ago. As we walked westward, it felt like stepping back through 185 million years of geological history.

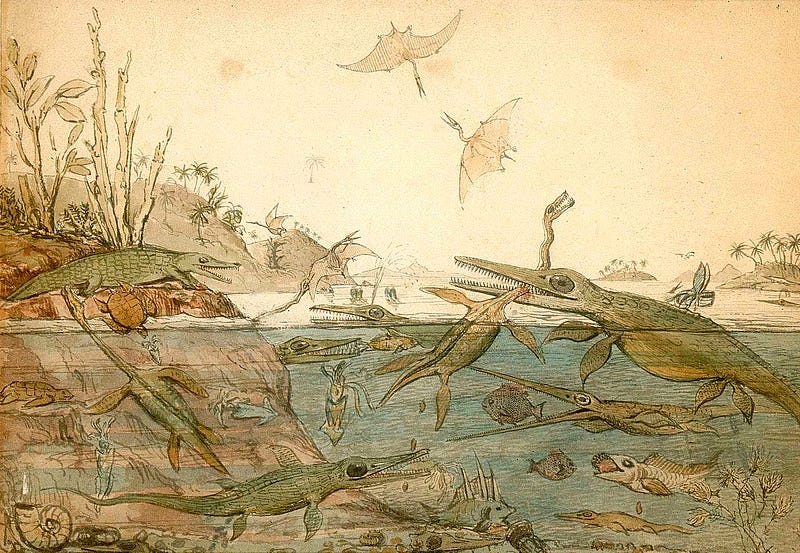

The early 19th-century fossil hunters and naturalists who explored the Jurassic Coast were filled with awe at the clear sequence of sedimentary rocks, each layer telling a story of the Earth's evolving history. They were equally fascinated by the remarkable fossils they discovered, including ichthyosaurs and pterodactyls—creatures that were unlike anything we see today, revealing the astonishing diversity of life that existed in ages past. In 1836, Reverend William Buckland, a leading geologist of his time, cautioned his audience that some of his findings were “more like the dreams of fiction” than the sober conclusions of careful study.

As a historian of evolutionary biology and director of the MIT Museum, I resonate deeply with Buckland and his contemporaries—the clerical naturalists who roamed this coastline in the 1820s and 1830s. My own journey from evangelical Christianity to a broader scientific understanding leads me to appreciate their pursuit of a unified worldview, drawing from diverse sources including scripture, empirical observation, and fieldwork. Their philosophy of “natural theology” is often hard to grasp today, as science and religion are frequently seen as opposing forces. Yet, this duality allowed Christian naturalists of various beliefs to collaborate and develop a coherent history of life on Earth, laying the groundwork for future geological studies and mentoring influential figures like Charles Darwin.

Today, the relationship between science and religion appears strained. Many believe they exist in conflict, and the possibility of harmonizing knowledge and faith seems elusive. Our intent in bringing students to the Jurassic Coast was to immerse them in the wonder that accompanied the groundbreaking discoveries of the early 19th century, helping them understand the complex relationship between science and faith that persists to this day. We hoped that this experience would inspire lessons relevant to our divided age, fostering a sense of awe that transcends belief systems and encourages contemplation about humanity's place in the universe.

Chapter 2: The Legacy of Buckland and Natural Theology

The first video, "Prescribing Awe," explores the profound impact of wonder and awe in bridging the gaps between science and spirituality, urging viewers to reconnect with the natural world's mysteries.

The early geologists, like Buckland, were captivated by the fossil finds along the coast, which hinted at a rich history of life that had long since vanished. Buckland, born to an Anglican clergyman, eagerly combined his religious studies with his scientific pursuits, conducting extensive field trips and amassing a diverse collection of geological specimens at Oxford. His time at the university was marked by significant contributions to geology, including his inaugural lecture in 1819, which advocated for the acceptance of geological sciences as compatible with Christian belief.

Buckland's interpretations often reflected a belief in divine harmony in nature. For instance, he viewed the evidence from fossilized remains, such as those uncovered by Mary Anning, as indicative of a preordained balance in nature. His interpretations were not merely scientific; they were infused with theological significance, attempting to showcase how geological findings could coexist with religious teachings.

Buckland's influence extended beyond his own work. He engaged with contemporaries like Adam Sedgwick, who also contributed significantly to the field. Sedgwick's outreach efforts included a memorable lecture to coal miners, connecting their daily lives to the grandeur of geological history and its moral implications. However, their attempts to reconcile science with religion faced challenges, particularly as conservative factions within the church resisted the encroachment of scientific inquiry.

The second video, "RX Side Effects," delves into the repercussions of the evolving relationship between science and religion, analyzing how cultural perceptions have been shaped by historical debates.

As the 19th century progressed, the natural theology of Buckland and his peers began to wane in popularity. This shift was partly a response to the growing influence of scientific naturalists who sought to separate scientific inquiry from religious doctrine. The publication of Darwin's "On the Origin of Species" in 1859 marked a pivotal moment, as it presented a secular framework for understanding evolution that diminished the perceived need for divine guidance.

The subsequent debate at the Oxford University Museum in 1860 between Huxley and Bishop Wilberforce epitomized the schism between science and religion. Ironically, the museum itself, a testament to natural theology, became a battleground for these opposing views. The building’s design aimed to unite the secular and sacred, yet the clash of ideologies overshadowed this vision.

Ultimately, the clerical naturalists' efforts to integrate scientific discoveries with their faith were overshadowed by a cultural shift that favored secularism. This historical conflict continues to resonate today, as we grapple with the implications of a society divided between science and faith. The legacy of Buckland and his contemporaries serves as a reminder of the potential for wonder and awe to bridge these divides, urging us to reclaim a more expansive understanding of the relationship between the natural world and the divine.